The process of making an artwork explained

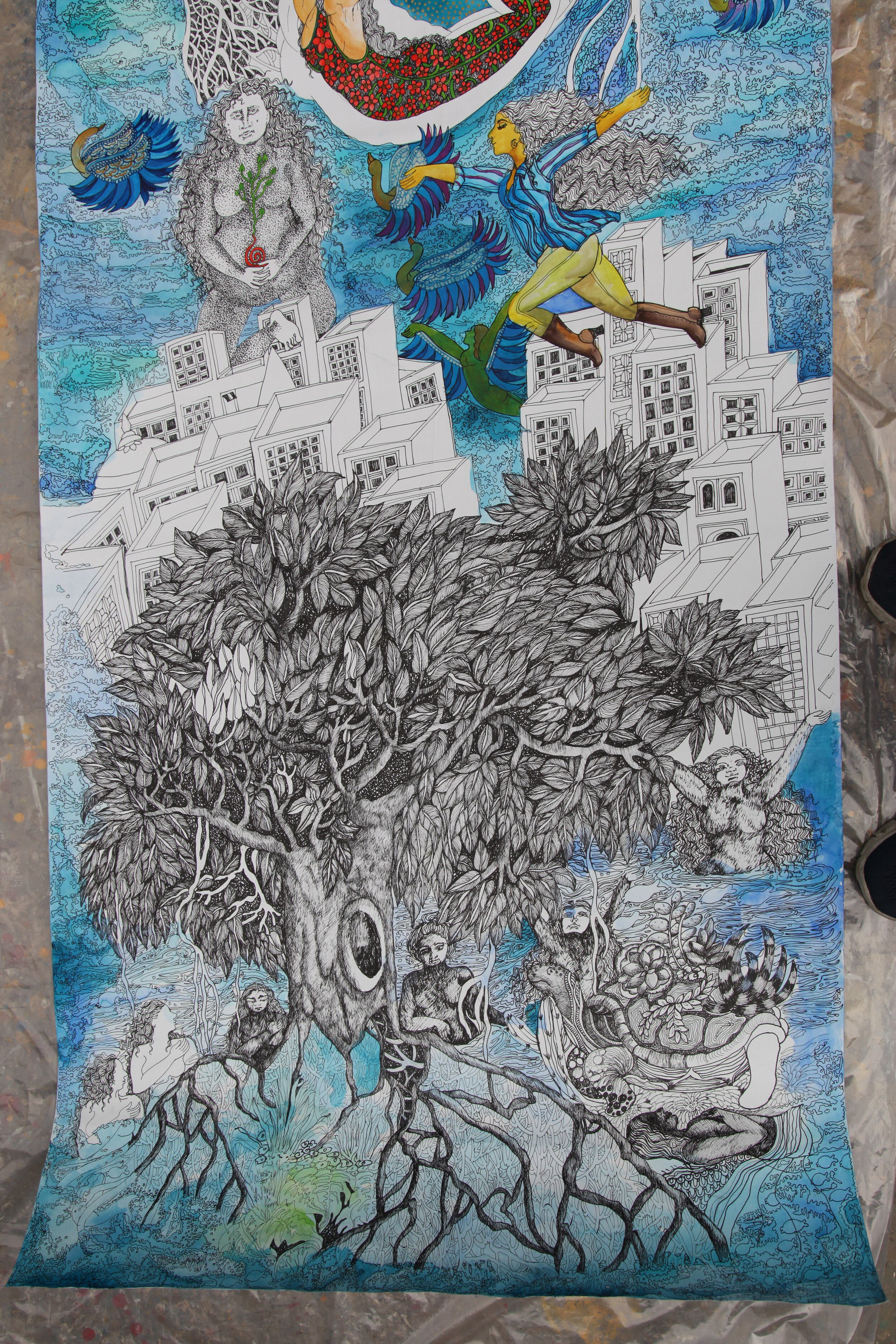

Hariti, work in progress

My mythical women have long symbolized fecundity, strength, and creative germination. In my most recent work, I engage with the leitmotif of femininity to chronicle stories of healing, nurturing, and salvation. As a visual artist, whose art practice explores the intrinsic feminine form and energy, I have been fascinated by mother goddesses. My present work Hariti is a continuation of the Golden Womb Series — Hiranyagarbha that engulfs and envelops everything in existence.

I first came across Hariti and Pancika at the Wei sanctuary and at Goa Gadja in Bali. Those images stayed me with and implored me to study further about this enchanting goddess- her form and iconography- as well as the ancient and contemporary beliefs that are alive today. I also encountered the living temples of Hariti at the famous Svayambhu Nath temple in Nepal where devotees approach her for a variety of reasons associated with childbirth, fertility, and curing and protecting children. Hariti is the tutelary grandmother goddess of Newari midwives and healers and is considered a form of Ajima in Nepal. Healers are locally called Mata (mother) and they are considered the very embodiment of the deity Hariti.

Hariti was also part of the Sixty-Four Yogini series that I had exhibited at the Sundar Nursery in Delhi, a UNESCO World Heritage Site last year. A sandstone sculpture of Hariti holding the cosmos and the Tree of Life and Bhudevi, Earth Goddess standing on a Makara marked the beginning of my exploratory journey as I understand her. My friendship with Janet and proximity with her work and research has also been crucial in arousing my interest in Hariti. The five of us do share a lot of our work with each other before we take it out.

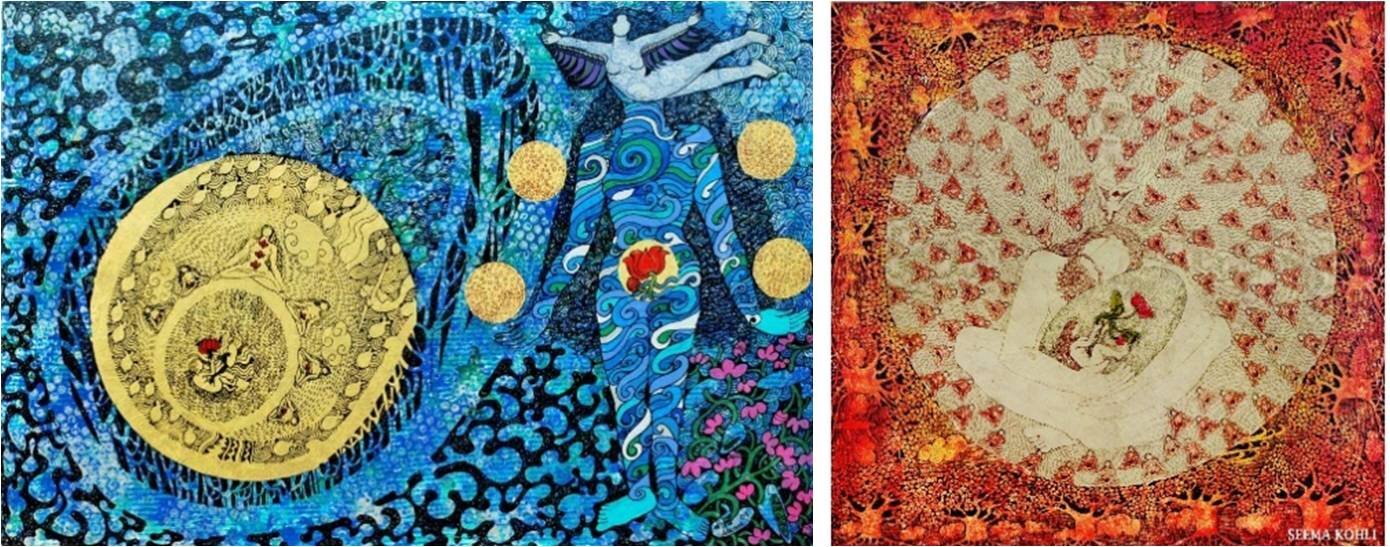

Hariti as Bhudevi in Seema Kohli’s series of 64 Yogini

My depiction of Hariti which I will share with you today stems out of the rich history of form, iconography, beliefs and stories associated with Hariti and birthing goddess over thousands of years.

Hariti ,goddess of Fertility and Panchika,god of Wealth. (2nd-3rd Century A.D).Peshawer Museum

Who is Hariti: Brief history

Though today the worship of Goddess Hariti is rarely observed in India, the cult of Hariti was especially important during the first century BC until its gradual decline in fourth century AD. Hariti and her consort Pancika, the Zaksha general (later Kubera, the god of wealth) belonged to the ancient Indic yaksha and yakshi cult – nature spirits associated with fertility and prosperity.

Kubera, Lakshmi, Hariti, Mathura

According to Buddhist legends, Hariti was a powerful ogress and a child-eating demoness. The name Hariti itself derives from the root word ‘Har’ (in Hindi ‘har lena’) meaning to steal or capture. She had hundreds of children (500 according to some accounts) who she loved but she would devour other children in the city of Rajgir or Rajagriha (a historic city in South Bihar where Buddha taught the early principles of Buddhism and where the first Buddhist Council was held) in order to sustain her own. Some texts give accounts of her previous birth to explain her behaviour. When Hariti or Hunashi, as she was known, was pregnant, she was made to dance by few people and as a result, she miscarried. Enraged with the loss of her unborn child, she vowed to cannibalise the children of Rajgir. Hariti is even said to have the power to cause epidemics such as smallpox. Her power and capacity to do harm evoked tremendous fear and attempts to pacify her through worship and sacrificial offerings were commonly practiced.

With the spread of Buddhism, a rationalist religion, the popular cult of Hariti was brought within its fold by creating a relationship of subordination. Buddhist narratives tell us that in order to make Hariti mend her ways, Buddha hid Hariti’s youngest son Pingala (Priyankara) under his begging bowl. A distraught Hariti realised the grief she must have caused hundreds of mothers by her demonic behaviour. She converted to Buddhism and became a protectress of children. Buddha assured her that his monks would assure that Hariti and her children were always well fed. This is the reason why Hariti shrines are located in monastery refectories (ie, the dining room of a monastery). Hariti in statutory form or painted on the wall is usually seen at the door or in the porch leading to the refectory.

Ferocious but a benevolent concrete Hariti at GoaGadjan Temple in Bali, 2013

Hariti was firmly entrenched in Buddhism and when the Chinese monk I-Tsing Yijing visited India in the 7th century, we found that Hariti was worshipped by monks and devotes in Buddhist monasteries. The teachings of Buddhism spread along the Silk trading route, the legend of Hariti too travelled along. We find paintings of Hariti in Japan, China, and Java islands.

My Hariti, my art

My Hariti resides in the skies, bears a look that is fierce and purposeful, and her long-tousled hair springs forth lotuses of knowledge. In her womb resides the celestial wisdom of the sun, the moon and the stars. Her attributes multiply to transforms her into a three-headed and multi-armed goddess. While her outstretched upper hands hold up the cerulean sky, her lower hands firmly rest on her bent knees offering balance. Squatting on her toes that have since grown into a dense capillary structure, she gives birth to a girl with a serpentine plait. The dense cross-hatched body of Hariti, the child-devouring demoness turned protector goddess, presides over the physical world from heaven.

Hariti by Seema Kohli

As over thousands of years, the legend of Hariti has created a multifarious circuit of local mythologies and beliefs creating similar forms in diverse regions, my Hariti too references and assimilates a rich thesaurus of ancient and modern images-making that produces a transcultural exploration of aesthetics, femininity, and religion.

Images of Hariti from early 1st century BC and 2 nd century AD from Gandhara - what is today northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, have shown her both in the sitting and standing posture, Hariti is typically depicted with five, six or eight children on her lap or shoulders or playing at her feet.

L) Seated Hariti, 2-3 century AD,Kushan, Yusufzai, Gandhara. British Museum, (R) Hariti Schist Stone, c 2nd century A.D. Skarah Dheri, Gandhara

This is related to the many Matrika sculptures we have in India as well as the sculptures from the Graeco- Roman world like that of Demeter and Isis Lactans. It is a universal iconography which in Christian art culminated into Madonna and child and In Hindu art as Krishna and Yashoda. Hariti is the soul behind the motherhood.

(L)Yashoda and infant Krishna, 12 century, Tamil Nadu, MET Museum, (C) Limestone-statuette-of-Isis-lactans-from-Antinoe (Egypt), 4th century CE, Dahlem-Museum, (R)Sistine Madonna, Raphael, 1512, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

She is sometimes shown along with her consort Panchika, the lord of the Yakshas who is potrayed in carrying a lance or with a wine cup or a money bag.

Hariti and Jambala (Panchika) , 5th century AD, Ajanta Cave 2, Aurangabad, Maharashtra.

However, my Hariti is not accompanied by children, and neither do I show her consort in my painting. For me, birthing is not limited to bearing offspring and neither is motherhood tied to childbirth. Through my work, I want to explore motherhood that is not biological, but creative motherhood. Women’s bodies have long been tasked with procreating and protecting. But for me, the act of nurturing is not exclusively a woman’s task. My three-headed Hariti denotes that her attributes live in all of us irrespective of the gender we identify with. The Idea of feminine is intrinsic.

The squatting pose of my Hariti draws from the rich repertoire of squatting woman or goddess giving birth popularly associated with fertility and motherhood in India. For example, Lajja Gauri, the lotus-headed fertility goddess was worshipped between the 6th to 8th century in Central India and Deccan. My previous work titled Lajja Gauri too borrows from the squatting goddess cult.

(Left above) Lajja Gauri, 6th century. (Below left) Carving of a squatting woman giving birth supported by two attendants, 18th century AD, South India, wood. Collection: National Museum, New Delhi along with my paintings done over a period of time.

My Hariti’s hair is long and free flowing to symbolise liberation and power while the little girl’s tightly knotted braid indicates her domestic shackles. The fierce and purposeful look with hands resting on her knees is acquired from some sculptures I have seen such as the one in the Allahabad museum and at Goa Gadja, Bali.

(L) Hariti, 1st- 2nd century AD, Allahabad Museum, (R) Hariti, Goa Gadja, Bali.

Next, I have depicted a pregnant woman birthing a city as Hariti was known as the Mother of Civilisations for sparing the lives of thousands of children in the city of Rajgir and protecting and saving countless lives in her later reformed life. The inspiration for this came from Hariti sculptures I encountered at Wei Sanctuary in Bali, Indonesia. Hariti’s iconography here was different from the earlier Gandharan sculpture – there are no children, instead she is pregnant with the whole world inside her. Her hair has transformed into foliage and her skin is tattooed with marine organisms and bounties of nature. She is the guardian of the universe. The surging belly of the woman on the upper right gives birth to civilisations while the child-free woman adjacent to her is impregnated with joyful liberation. Mothers and non-mothers both find a place in my visual narrative.

The lotus or flower buds that germinate from the womb of the goddess is a feature that spans across my works. Through the visual language of lush abandonment, feathered wings, and flowing tresses, the lotuses and clouds, and layers of overlapping figures, I intend to express that we all emerge from one single womb, and this golden womb is the amalgamation of yin and yang, positive and negative, man and woman.

We all belong to The Golden Womb- to one single space that we all share in one home that is this world, either through our traditional concept of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, or the origins and continuous existence of life through the cosmic Tree of Life.

There is one mother nature and we are are all from her. “Tree of Life” a bronze sculpture by Seema Kohli.

In the lower register of the painting, I have shown six-headed Skanda Kartikeya in an iconic form - as a deep-rooted and bountiful tree. Historians such as Dr. Naman Ahuja in their recent iconographic examinations have found Kartikeya to be one of Hariti’s children. Kartikeya had his origins as a demonic being, a child afflicting deity who has to be propitiated through worship. It was only later that he is incorporated into the Brahmanical pantheon and becomes the son of Shiva.

Kartikeya was raised by six foster mothers or Krittikas who found the infant at the banks of Ganga. These Krittikas too are the embodiment of Hariti as they protect, nourish and care for the infant Kartikeya. Motherhood here is not biological but a sentiment.

Six Krittakyas mothers of Kartikyae at Goa Gadja in Bali, 2013

In using the anionic fig tree for Kartikeya, I reassert the deep symbolism associated with the tree in Hindu and Buddhist philosophy. At the same time, the lone green tree is but a microcosm of dense enchanted forests. It is in the abundant forest, the lap of nature where gods and goddesses, rishis and sadhus, demons and nature spirits dwell and complex transformations unfold.

In its visual metaphor of Kartikeya as a tree, the six-headed Kartikeya is reimagined as a deep-rooted and bountiful tree, an interesting departure from the customary feminisation of nature. Here, I offer a double ode – a tribute to the six Krittikas and to the women eco warriors. For it is the women forest dwellers in India who have since centuries stood guard by throwing their bodies in front of predatory axes. We know about the Chipko Movement too. Their protests against mindless felling of forests continues unabated with the only tools they have -courage and persistence. They are the glorious champions of ecological conservation.

Hariti and the six matrika’s

The coexistence of forests and cities visualised as rows of buildings stacked together like piles of cardboard is for me the balance we need to strive for between nature and culture. Only with this equilibrium can there be pulsating life symbolised by the luminescent heart above them.

Through my contemporary portrayal of Hariti, I want to demonstrate that it is a woman who creates, cares and protects and this woman resides in all of us. As the divine creation saga unravels, I insert myself in the narrative (lower left of the painting) with my hand on my chest and my head sunk in her buttery bed, as the creator of the canvas of life.

Hariti-work in progress

Artwork and Concept : Seema Kohli

Text and Edit : Habiba Insaf